Intermittent Explosive Disorder: Understanding Causes of Rage

Experiencing sudden, overwhelming bursts of anger can be a frightening and confusing ordeal. You might find yourself grappling with intense emotions that feel disproportionate to the situation, leaving you with guilt and shame afterward. If you've ever asked, "Why does this happen to me?", you are not alone. This question is the first step toward understanding. This article delves into the complex origins of Intermittent Explosive Disorder (IED), exploring the biological, psychological, and environmental factors that contribute to this challenging condition. Understanding these roots is a vital step toward taking control and finding the right support.

For many, the journey begins with self-reflection. Gaining initial insights into your emotional patterns can be empowering. A free, confidential assessment can provide a structured way to begin this process, offering a private space to explore your experiences before seeking professional guidance.

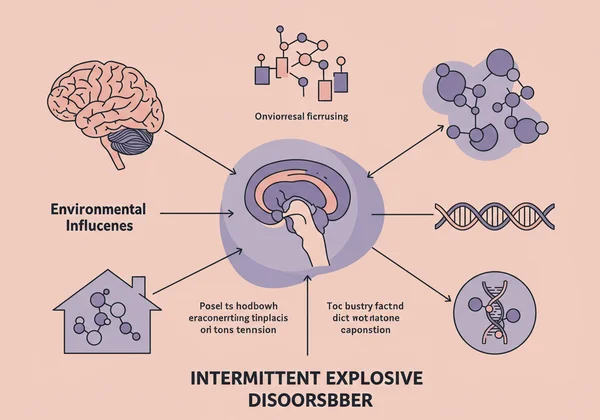

The Biological Underpinnings of Intermittent Explosive Disorder (IED Causes)

While explosive anger can feel like a personal failing, it's important to remember that biology often plays a big part. The foundations of IED are frequently linked to our innate neurobiology and genetic makeup. These aren't choices; they're predispositions that can make emotional regulation harder for some. Understanding IED's biological basis helps remove stigma, showing it's a legitimate health condition.

Genetic Predisposition & Family History: Is IED Inherited?

One of the most common questions is whether a tendency for explosive anger can be passed down through generations. Research suggests that there is indeed a genetic predisposition to impulsivity and aggression. Studies on families and twins indicate that IED has a significant heritable component. If you have close relatives who struggle with explosive tempers or impulse-control disorders, your own risk may be higher. This doesn't mean IED is inevitable, but it suggests that some individuals may be born with a higher sensitivity to developing the condition, especially when combined with other risk factors.

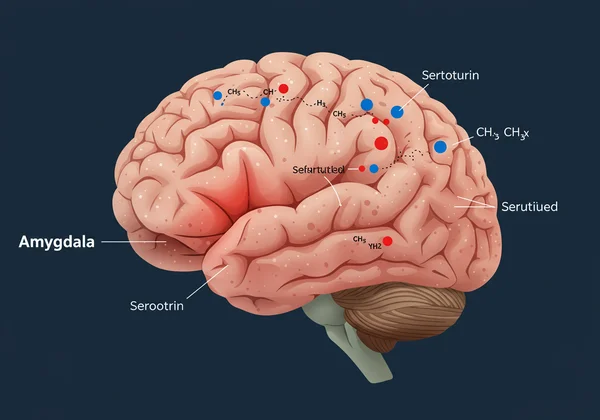

Neurological Factors: Brain Differences & Chemical Imbalances

Beyond genetics, neurological factors are central to understanding IED. The brain is where our emotions are regulated, and even subtle differences in its structure and chemistry can have a major impact. Two key areas are often implicated:

- The Amygdala: This part of the brain acts as a threat detector. In individuals with IED, the amygdala may be overactive, causing them to perceive threats where others might not and triggering a rapid, intense "fight or flight" response.

- The Prefrontal Cortex: This is the brain's executive hub, responsible for reasoning, impulse control, and moderating social behavior. In people with IED, the prefrontal cortex may be less active or have a weaker connection to the amygdala, making it harder to calm down and override aggressive urges.

Imbalances in brain chemicals, particularly serotonin, are also believed to contribute. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that helps regulate mood and inhibit impulsive behavior. Lower levels of serotonin have been consistently linked to increased aggression and difficulties with emotional control.

Environmental and Psychological Factors in Explosive Anger

Biology might create a predisposition, but our life experiences and psychological makeup truly shape how we express anger. For many, patterns of explosive anger are shaped by the environment they grew up in and the coping skills they developed over time. These factors are not about blame; they are about understanding how our past influences our present reactions.

The Impact of Childhood Trauma and Adverse Experiences

Exposure to childhood trauma is one of the most significant environmental risk factors for IED. Growing up in a household with verbal or physical abuse, witnessing violence, or experiencing neglect can profoundly affect a developing brain. These adverse experiences can teach a child that the world is a hostile place and that aggressive outbursts are a normal or necessary way to respond. This can lead to hypervigilance and an ingrained pattern of reacting to stress with disproportionate anger in adulthood.

Learned Behaviors: Modeling Aggression & Coping Mechanisms

Our earliest relationships often serve as blueprints for our own behavior. If children observe parents or other authority figures responding to frustration with explosive rage, they may internalize these learned behaviors as the primary way to handle difficult emotions. Without exposure to healthy coping mechanisms—like communication, problem-solving, or self-soothing—aggressive outbursts can become a default, automatic response to stress or conflict.

The Role of Co-occurring Mental Health Conditions

IED rarely exists in a vacuum. It often overlaps with other mental health challenges. These co-occurring mental health conditions can exacerbate the symptoms of IED or be risk factors for its development. Common co-occurring disorders include:

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- Depression and Bipolar Disorder

- Anxiety Disorders, including Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Substance Use Disorders

These conditions can lower an individual's threshold for frustration, increase impulsivity, and make emotional regulation even more difficult, creating a complex cycle that requires comprehensive attention.

Identifying Your Risk: Key Factors Contributing to IED Development

Recognizing the intermittent explosive disorder risk factors in your own life is a powerful step toward self-awareness. It allows you to connect the dots between your experiences and your current challenges. Several key factors can increase the likelihood of developing IED, many of which we have already touched upon.

If you recognize some of these factors in your life, it may be helpful to explore your anger patterns through a structured tool designed to provide clarity.

Age of Onset: Does IED Get Worse With Age?

Many people wonder if IED gets worse with age. Symptoms of IED typically begin in adolescence, often before the age of 20. If left untreated, the patterns of explosive behavior can become more entrenched over time. While the frequency or intensity of outbursts might not necessarily increase, the consequences—such as damaged relationships, job loss, or legal trouble—often accumulate and worsen. However, the opposite is also true: with awareness and proper treatment, individuals can learn to manage their anger and improve their quality of life at any age.

The Influence of Stress, Substance Use, and Triggers

While biological and environmental factors create a predisposition, current life circumstances are often what trigger explosive episodes. Stress, in particular, has a major impact. High levels of chronic stress can erode a person's ability to cope, making outbursts more likely. Substance use, particularly alcohol, is another major factor. Alcohol lowers inhibitions and impairs judgment, making it far more difficult to control impulsive, aggressive urges. Identifying personal triggers—specific situations, people, or feelings that precede an outburst—is a critical part of managing IED.

Navigating Your Understanding of IED: Your Next Steps

Understanding the causes of Intermittent Explosive Disorder is not about finding an excuse; it's about building a foundation of self-compassion and creating a roadmap for change. We've seen that IED is a complex condition stemming from an intricate mix of genetics, brain chemistry, past trauma, and learned behaviors. Recognize that IED isn't a personal failing; it's a treatable mental health condition.

Recognizing these factors in your own life is the first, most courageous step. The next is to seek further insight. If anything in this article resonates with your experiences, consider taking a safe and private step to explore them further. Take the first step with our free, confidential anger and impulsivity self-assessment to gain personalized insights that can serve as a starting point for a conversation with a healthcare professional.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Causes of IED

What causes intermittent explosive disorder?

Intermittent Explosive Disorder (IED) is believed to be caused by a combination of biological, environmental, and psychological factors. Biologically, it's linked to genetics, differences in brain structure (like an overactive amygdala and underactive prefrontal cortex), and imbalances in neurotransmitters like serotonin. Environmentally, growing up in a home with verbal or physical abuse and learning aggressive behaviors are major risk factors.

Does IED get worse with age?

If left untreated, the negative consequences of IED often get worse with age due to accumulated damage to relationships, careers, and legal standing. However, the condition itself is treatable. With therapy and sometimes medication, individuals can learn to manage their anger and impulsivity effectively, meaning the prognosis can improve significantly with intervention, regardless of age.

What happens if IED is left untreated?

Untreated IED can have severe consequences across all areas of life. It can lead to relationship breakdowns, divorce, job loss, school suspension, financial problems, and legal issues, including assault charges. It also increases the risk of self-harm, suicide attempts, and developing other mental health conditions like depression, anxiety, and substance abuse. It is crucial to seek help to mitigate these serious risks.

How do I know if I have IED?

The only way to know for sure if you have IED is through a formal diagnosis from a qualified mental health professional. However, you can start by looking for key signs: recurrent angry outbursts that are grossly out of proportion to the trigger, verbal aggression or physical assault, and feeling a sense of relief or release during the outburst, often followed by intense regret or shame. If you're questioning your anger, a confidential intermittent explosive disorder test can be a valuable first step to organize your thoughts before speaking with a professional.